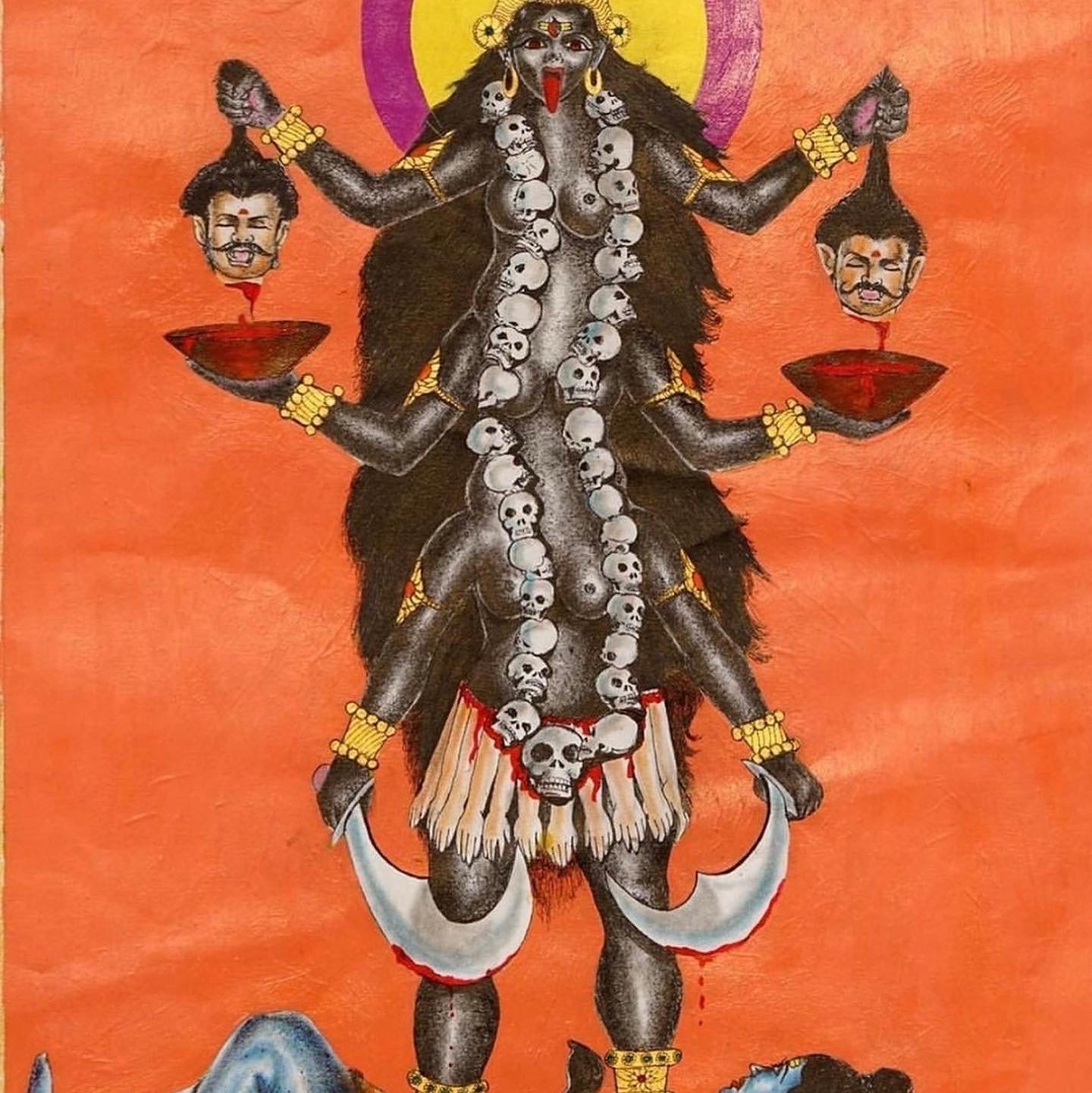

Eating Patriarchal Evil with Kali

In times of war and conflict, the opposites constellate in the collective psyche and the moral, social and political duty of each of us is to hold the tension of opposites and to withdraw the projection of evil onto the “barbaric other”. The myth of Kali can teach us during these intense times of war and suffering.

on The Duty of Withdrawing Projections in Times of War and Conflict

In the myth of Kali, the dark Hindu goddess of death and transformation, the patriarchal demons have gone mad, drunk on power and destruction. None of the goddess forms is able to stop them, they have grown so large and out of control that they are indeed set to destroy the entire creation. It is at this moment that Kali is born out of the already powerful Durga; this crone goddess, dark as coal appears with a lolling tongue, eyes wide and a sickle in the hand she starts to slaughter and behead the demons. But, this seems to only make matters worse as for every blood drop that is shed, a thousand demons emerge once it hits the soil. The demonic patriarchal powers multiply beyond control. The only solution is to "eat the blood" before it hits the ground. And so, Kali does exactly that. As she beheads, she eats the evil, takes it inside herself to save creation from total destruction.

This moment in the myth, the image of the blood drops, creating a thousand more demons every time it hits the soil, has come to my mind many times as I watch the news and horror of destruction and war, suffering and killing in the Middle East. The blood spilled for the sake of revenge, power or total annihilation of a perceived enemy. And every time this blood is spilled, a seed of hatred is sown into the world soul. The demons only multiply and multiply during war. No enemy is eliminated, no villain is killed with the shedding of blood.

kali’s wisdom

What then, does this moment in the myth teach us? After 6 years of working with the Kali myth in-depth with my colleague Gauri Raje, and seeing the myth expand and flesh out in our psyches as well as the women we have worked with, we come to a moment in history where more than ever the myth is played out on a global stage. Psychologically, it does not matter on whose "side" you stand in the Middle Eastern war (even though it will matter very much politically and socially). But for the psychological burden on each of us, it does not change; on either side there is a perceived demon, an enemy that needs to be destroyed and eliminated. The Kali myth teaches us that eliminating evil, killing evil only breeds more evil. The spilling of blood makes fertile ground for bitter seeds of hatred to grow in the human heart that, over time turn the tree of life into a tree of death. What Kali teaches us then, is that we must take it in. We must eat the blood of the demon. We cannot project evil to the other and "eliminate" it. We must take back the projection and take it in, become part of its ecology, so to say. Herein then lies the great capacity for compassion; for only when we have tasted our own shadow and evil, can we contribute to the healing of the world soul from the destructive and tyrannical powers of revenge, oppression and destruction. Kali as goddess and archetypal force wields a sword; she kills what is destructive and evil. But much like a bodhisattva, she then takes it in, she eats evil in order to contain it in the black void of her body. This comes with a price as she then becomes totally drunk on her own power, or perhaps this mad power she swallowed now takes possession of her. After a furious dance battle with Shiva, it is only—and finally—the force of compassion and mercy—her impetus for tenderness and nurturance—for a Shiva-turned-infant that can calm her down and bring her, and the world soul, back into balance.

The crone goddess Kali eats the Asura demons with her lolling tongue

Psychologically, this means that there is a great burden on us all as we witness the unfurling of a world in conflict and war. Each of us who has the consciousness and ability has to take in one droplet of this evil, has to swallow it and make it our own; that is, to take back the projections we have cast on the "other" and weave ourselves back into the ecology of what has become rejected and evil within ourselves. By this great act of compassion, we begin the task of ceasing the destructive powers of a droplet of blood. This is no easy task as the average wo/man will find it difficult to imagine that the evil they witness on the world stage is part of us, and is living in the dark basements of our own psyche. This is why Jung said as he did in this now famous quote: "The world hangs on a thin thread, and that is the psyche of man.” Unless we take back the projections of the "barbaric other", the world soul will continue to suffer alone, and this great time of transition will be lost to modern wo/man's vanity and ignorance.

““The best political, social, and spiritual work we can do is to withdraw the projection of our own shadow onto others.””

Numinous Experiences of the Feminine: in Conversation with Anne Baring

A dialogue between Anne Baring and Faranak Mirjalili about the mysticism of the Feminine.

by Anne Baring & Faranak Mirjalili

This dialogue between Anne Baring and Faranak Mirjalili dives deep into the mysticism of the Feminine, and what the importance is of experiencing the Godhead as ‘She’ in a time when the emergence of the feminine principle is of vital importance.

Books mentioned and recommended in the talk:

Occidental Mythology: The Masks of God Vol. 3, by Joseph Campbell (1964)

Boethius: The Consolation of Philosophy by Victor Watts (trans.) (2000)

Sophia: Aspects of the Divine Feminine Past and Present, by Susanne Schaup (2004)

TRANSCRIPT

Faranak: Dear Anne, let’s dive right in and start with definitions. How would you define a spiritual or as Jung would say a ‘numinous’ experience?

Anne: It is something that happens unexpectedly, unusually, out of the blue. It may happen in a dream. It might be a visionary dream or it might be something that just happens to people as they're walking along the street or cooking their lunch or whatever.

A sudden insight comes, a sudden opening of the door into another dimension. And then they may hear a voice or they may even speak with that voice, whatever it might be, or it may be a message, a direct message telling them to do this or that. I can't really define it because it's very broad. There are many kinds of spiritual experiences that people have had.

Many people have them when they go out into nature, in the woods. Like David Attenborough, he says, "go and just sit in nature and you will hear and see things that you didn't hear or know before." So on many levels, you get this experience of a deepening consciousness or an opening consciousness to another reality or a deeper reality than the one we're living in or seeing deeper into this reality, perhaps.

Faranak: In your book The Dream of the Cosmos, you share your dream of the cosmic woman as a profound dream and guiding experience for your life's journey and research. Would you say this was a numinous, or sacred experience? Can you tell us a little bit more about this?

Anne: Yes, absolutely, no question about it because it was. I've never had a dream like that before or since. It was definitely something coming to me from the universe, which I took as a message telling me what I needed to do. And it had nothing to do whatsoever with the religion, with Christianity which I was brought up in.

It was a vision of a cosmic woman, possibly the way people in the past have had a vision like Apuleius had the vision of Isis, for example. It was that kind of experience completely out of the ordinary, completely revelatory, and visionary. It was a vision.

Faranak: What would you say gave this experience a numinous feeling, compared to other dreams or experiences of a feminine figure that may have inspired you? Could you define the difference?

Anne: The difference is that it was a vision of a woman that I couldn't associate with any specific goddess. I thought; is this Demeter, is it Aphrodite? Is it Isis? But none of those fitted what I was seeing. So it came absolutely unexpectedly out of the blue. And eventually, I associated it with the feminine aspect of God, not in the Christian tradition but in Kabbalah.

Because I was led to that tradition and the Shekinah of Kabbalah was the only image or the only word that fitted the power of that experience. It wasn't a goddess. It was something far beyond a goddess, it was the universe itself speaking in feminine mode.

Faranak: So it did in a way eventually lead you to a lost or hidden religious tradition one could say?

Anne: Well, it isn't really lost but it's one that isn't very well known in the West. In the West, we're more familiar with Christianity. I think Jewish people know of it possibly if they're interested, if they're drawn to the mystical aspect of their own religion, they will know about it. And it's taught all over the world. And I had a teacher in England called Warren Kenton years ago, whom I studied with. So it's not something that's unknown but it's something that isn't well known, put it that way.

Faranak: In your book, you show the reader throughout the book how the loss of the lunar ‘participation mystique’ and this shamanic connection to nature and the feminine has damaged the very fabric of life and the World's Soul. Do you think that this disrespect and violence against the feminine and nature has also distorted and ruined the inner images of feminine deity and our ability to experience Her in these more numinous or divine images?

Anne: Well, I think that Christians have the Virgin Mary to fulfil a certain aspect of the divine feminine but they certainly have lost the feminine aspect of deity; all the patriarchal religions have lost that. And it was that that connected us to nature, because the ancient goddesses, particularly goddesses like Isis and Artemis of Ephesus, represented not only nature but the whole of the cosmos. And this is something we completely lost.

We have no connection with the cosmos. We may have a connection through the Virgin Mary with an image but she is not a deity and she's not the feminine aspect of the divine as far as I can understand. Although she has been raised to that in the Catholic religion in 1950 and 1954; she was raised to the level of the male deity but people don't know about that.

They don't know about the Papal Bull in 1950 and the Encyclical of 1954 which made her "Queen of Heaven." So she has had restored to her the ancient title that Isis held; Queen of Heaven and also Inanna before her was Queen of Heaven. So that does help but still, a big thing is missing which is the connection to nature. And also the sacredness of nature that has gone completely and needs to be brought back.

Faranak: Because in the Christian thought there's still the elevation of the heavens above nature. So when she is put up into the heavens the question is, is she then detached from earth and seen as above it?

Anne: Well, she was taken up body and soul so the body was included there, but not the whole of nature. So you'd really have to go into the theology of it I think to understand it better. But on the other hand, Pope Francis in his Encyclical of 2015, absolutely rescued nature from the oblivion in which it has existed for a very long time. He restored it to its sacredness and that was a tremendous thing to do.

And I'm really tremendously grateful to him for doing that. It's a long Encyclical but it's full of wisdom and full of reproach that we have neglected our relationship with nature and haven't treated it properly. So he understands at a deep level what's happened.

Faranak: What I wonder is if I look at the experience that you had and other experiences of contemporary women, like the ones I've had with the Persian Goddess Anahita is; do we need these documentations so that we are able to even perceive Her? Let me ask it in this way: if all the images have been wiped out, where does our imagination find space to receive these images of Her? Has the wiping out of her sacred texts and her temples also damaged our imagination and ability to perceive Her in the imaginal realm?

Anne: Yes. I think I would absolutely agree with that. It has damaged the imagination. That's a very good phrase because we have no image that we can connect with which brings nature and the cosmos into one figure, one divine figure. So we haven't got anything that we can start with as it were. We have to go just finding as I have with these ancient descriptions of visions that people had, that have been a great help.

And I put them into my book, The Divine Feminine, I brought the vision of Apuleius of Isis. And of course, people did have visions and many more visionary experiences. The Egyptians certainly did, the Greeks certainly did, the Sumerians did. So really we're a culture that is bereft of visionary experience. It's missing. So there isn't anyone who can say, "Oh, so-and-so had a vision of something the other day, we can all discuss this and share it and pass it around through the internet."

There is in Marion Woodman's work, there are dreams that she brings of the Black Madonna that people have had. So that was something Jungians would know about for instance, but nobody outside the Jungian circles would know that people were having these visions of the Black Madonna. And if I hadn't put my vision into my book, nobody would know of my vision. It is a tremendous vision that changed my life, absolutely.

Faranak: So these images of the feminine that are retrieved and restored and shared, they actually can start to heal the damaged imagination.

Anne: They could and possibly if we listen to children who might have visions of the Virgin Mary which indeed they've had, they have been paid attention to, and the visions of Fatima in Portugal and Medjugorje in Yugoslavia they've been recorded. So there has been something but it hasn't spread beyond the Catholic population.

Faranak: This brings us to the second part of the interview which I've divided into three parts. It's about the importance of experiencing God or deity as feminine. So firstly, what do you think the importance is for a woman to experience God as feminine?

Anne: Well, I think it's very important because then she can understand, as I did, that she is made in the image of the divine feminine. She can see her body as a manifestation of the divine feminine in this material dimension of experience. So I think it would be a tremendous help if she had one as I did, or other women have had them, perhaps we don't know. It's a tremendous anchor in a world where we really don't know what we're doing, why we're here.

Faranak: Yeah. And what do you think the importance is for a man to experience this feminine side of deity?

Anne: I think it's equally important for a man because men have been brought up with the monotheistic image of God for nearly 3000 years or two and a half thousand years if you include the Judaic tradition, that's a long time to be imprinted with the image of only a male God or the male aspect of deity. So I think it's absolutely essential that men also have this experience with the feminine aspect of deity and that it is numinous for them.

It will be almost shocking that this is something that they've neglected and they haven't realized that they carry this feminine aspect of life within their own nature, what Jung called the anima, they have the anima within their nature.

Faranak: So when you say shocking, why do you say shocking?

Anne: Well, it would be a shock to many men to discover that this is a sacred image and they had never thought of it before in that way, possibly. And so it's shocking in the sense that it's unusual, strange, different.

Faranak: That it evokes something.

Anne: And it will stir something in them or get them to ask questions possibly, or make a relationship with this image and ask that image what it wants of them, why is it appearing to them.

Faranak: There have been men in the past, as you shared with me before that have had these experiences. Would you like to talk about one of them in particular that has touched you?

Anne: Well, they've all touched me really. First of all, there's a very ancient one, 2000 BC of a King in Sumeria who had a dream. And he went to the temple of the goddess and asked the goddess to give him the explanation of the dream. And she gave it to him and she told him that he was to build a temple. And in the dream, he had an image of a donkey carrying material for building and she said the donkey is you. You're carrying the material and you have to go and build a temple to my brother, the God Ningirsu.

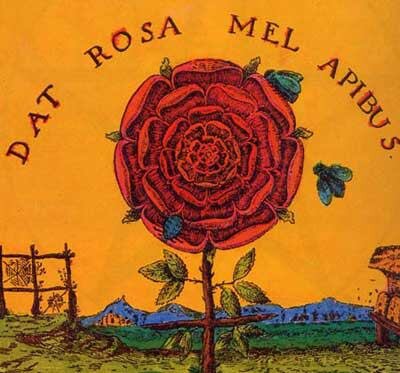

So that was a lovely dream to come down all this time. And that's recorded in Joseph Campbell's book; Occidental Mythology. He's a fantastic chronicler of history so one always finds something there. And then there was Apuleius' vision of Isis and Apuleius was an Egyptian that was living in the second century of the Christian era. Who lived, I think in Rome, who was is an initiate the Mysteries of Isis. And he writes this, such a beautiful description.

He writes: "The apparition of a woman began to rise from the middle of the sea with so lovely a face that the gods themselves would have fallen down in adoration of it. First the head, then the whole shining body gradually emerged and stood before me poised on the surface of the waves. Her long thick hair fell in tapering ringlets on her lovely neck and was crowned with an intricate chaplet in which was woven every kind of flower. Just above her brows, shone a round-disc like a mirror or like the bright face of the moon which told me who she was.

Vipers rising from the left hand and right-hand partings of her hair supported this disc, with ears of corn bristling beside them. Her many-coloured robe was of the finest linen; part was glistening white, part crocus yellow and part glowing red. And along the entire hem, a woven bordure of flowers and fruit clung swaying in the breeze. But what caught and held my eye more than anything else was the deep black lustre of her mantle.

She wore it slung across our body from the right hip to the left shoulder, where it was caught in a knot resembling the boss of a shield. But part of it hung in innumerable folds, the tasselled fringe quivering. It was embroidered with glittering stars on the hand and everywhere else and in the middle, beamed a full and fiery moon. On her divine feet were slippers of palm leaves, the emblem of victory. And these are the words that she spoke to him.”

"I am nature, the universal mother, mistress of all the elements, primordial child of time, sovereign of all things spiritual, queen of the dead, queen also of the immortals, the single manifestation of all gods and goddesses that are. My nod governs the starry heights of heaven, the wholesome sea breezes and the dreadful silence of the world below. Though I am worshipped in many aspects and known by countless names and propitiated with all manner of different rights yet the whole round earth venerates me."

Now that was something, if you had a vision like that, what would you do?

Faranak: I know…this is mind blowing on so many levels.

Anne: Yes. And she speaks as a cosmic…

Faranak: Authority, really.

Anne: Authority, total authority, "the whole round earth venerates me." She's no mean little tiny goddess there.

Faranak: And she's not bound to the earth. She is the axis of the entire creation here.

Anne: Exactly, she is. She speaks from the divine centre of the universe. And what it did to him, it's very funny what she told him to do because he was in the form of an ass at this time when he had the vision. And he was very worried that he'd never go back to his human form. And she told him to go and stand in the procession and to watch the high priest who would be carrying a garland of roses. I think he had the vision after he had been changed back from an ass into a man, not before, so this paragraph needs changing a bit.

And Apuleius was to rush up to the priest and take a big bite out of the garland of roses. And if he did that, he would be changed back into his mortal form. So he did this and of course, he changed back into a completely naked man. And he had to be covered with a cloak but he describes the bliss of chewing these rose petals and feeling himself changed back from an ass into a human being, into a man.

I mean, that was so thrilling and so exciting and described so beautifully in his book that one can't help laughing because it must've been a very funny spectacle. The high priest was horrified and shocked and then amazed at what was happening in front of him. And all the people in the crowd were stunned….what an experience for everybody!

Faranak: The sense of humour says something about the nature of the goddess…

Anne: It's very grounded, absolutely grounded.

Faranak: I was also wondering what you thought about the description of the goddess; ‘the finest linen, the glistening white, the crocus yellow’ it's all very sensuous.

Anne: It is, and very vivid and you could almost touch it. You can feel the quality of the robe in the finest linen of the robe and then her black over mantle.

Faranak: Exactly and that really, this evokes the senses really. It brings the senses and the imaginations to life when one reads a vision like that. It does something to the senses internally as if flowers are popping out of one's imagination.

Anne: Yes, I think absolutely. And with the vipers supporting this disc above the head and everything, and that's very brilliant imagery, very careful description really. And it's exciting for the body to be included because it's about the bodily form of the flowers and nature, everything is included there. Nothing is left out and she's even got glittering stars on the hem.

Faranak: I think that if we speak of loss of images and the damage that is done to our imagination if the senses, the body and the earth have always been condemned as a place of evil, whereas if you read this, there's nothing evil about this.

Anne: No, there is nothing fallen, nothing sinful, nothing bad about this at all. This is glorious!

Faranak: Exactly.

Anne: And that really excites the imagination because the imagination is part of all of this — to be able to describe what is coming from this man's imagination. And he's seeing it with his imagination if you like. And I think there's a wonderful alchemical saying; “Imagination is the star in man”— a beautiful saying.

It really is our starry body possibly, the imagination.

Faranak: Yes, beautiful. Let’s continue with the next historical experience you wanted to share with us.

Anne: The next one is quite different. It comes from a wonderful scholar called Boethius, who lived at the beginning of the sixth century of the Christian era. And he had been taken prisoner by a barbarian emperor called Theodoric. And he was waiting in the cell for his execution. He was very depressed as you would be if you were waiting for your execution and he was crying I think, and mourning that his life was coming to an end.

And then suddenly he says this in the manuscript that was called The Consolation of Philosophy. And God knows how it got out of that prison cell intact because it's five whole books of writing…it's a lot of writing. Anyways he says this, "while I was quietly thinking these thoughts over to myself and giving vent to my sorrow with the help of my pen, I became aware of a woman standing over me.

She was of an awe-inspiring appearance, her eyes burning and keen beyond the usual power of men. She was so full of years that I could hardly think of her as my own generation. And yet she possessed a vivid colour and undiminished vigour. It was difficult to be sure of her height. For some time, she was of average human size while at other times she seemed to touch the sky with the top of her head. And when she lifted herself even higher, she pierced it and is lost to human sight.

Her clothes were made of perishable material of the finest thread woven with the most delicate skill. And later she told me that she had made them with her own hands. Their colour was obscured, however, by a kind of film as if with long neglect like statues covered in dust. On the bottom hem, could be read the embroidered Greek letter Pi and on the top hem, the Greek letter Theta. Between the two, a ladder of steps rose from lower to the higher letter.

Her dress had been torn by the hands of marauders who had each carried off such pieces as they could get. And there were some books in her right hand and in her left hand, she held a sceptre. Tears had partly blinded me and I could not make out who this woman of such imperious authority was. I could only fix my eyes on the ground, overcome with surprise and wait in silence for what she would do next.

She came closer and sat down on the edge of my bed and I felt her eyes resting on my face, which was downcast and lined with grief.” And she began to speak to him at great length explaining things that were perplexing him really going deep into philosophy, and explaining why evil exists, for example.

I can't go into it, it's too long because there are five books but this book had a tremendous influence on the so-called dark ages. And his book was particularly valued by Charlemagne, in Charlamagne's court. So this is another visionary experience just when he perhaps expected nothing, except the jailer coming to fetch him for execution.

And he had this marvellous vision, which was so powerful that it influenced 300 or 400 years of people who were searching for wisdom themselves. And she was called ‘Philosophia' but really she is Sophia or Divine Wisdom—that's who she was speaking to him.

Faranak: Extraordinary vision, again, amazing images.

Anne: A very powerful vision. And again, it says that her dress had been torn by the hands of marauders. So his time, nobody really bothered anymore with Wisdom.

Faranak: Covered in dust.

Anne: Covered in dust, like statues covered in dust and yet her robe was woven with the most delicate skill. So there again, you get the imagination working and you'll get the physical image on the touch of the material almost like you did in Apuleius' vision. It's very real, very present. And many artists did pictures of it which got into the Books of Hours and things like that.

I've always loved that. I've known about that since I was 20 and I've looked over my bookshelves for it, for the book. And it's a very small penguin book that looks like this.

Faranak: That's an image of the vision. Yes. Boethius: The Consolation of Philosophy.

Anne: . I found it on one of my shelves finally, after about two hours of looking because I hadn't looked at it for many years until you asked me to bring up these visions.

Faranak: Thank you. It’s extraordinary. I think I was wondering what you thought of what he meant by the fact that “she made her garment with her own hands”…that was so touching.

Anne: Well, she would do if she is 'Divine Wisdom', she would be making the fabric of life including her own robe. Yes, she would be doing that.

Faranak: I like that because if we think of the idea of God as a male ‘creator deity’ who created the creation including the feminine—this vision goes against that as she says “I created it with my own hands".

Anne: Yes, exactly.

Faranak: It does go counter to that idea of God, the creator, here we see the goddess as the creatrix, even of her own robe.

Anne: Of her own robe. Yes. That's very clever that you should pick that up.

These are tremendous visions and they lasted for a very long time. I think Boethius had his about 300 years after Apuleius, not very long really. And then we have a great gap really. And right away we have Hildegard of Bingen in the Christian tradition. And we have the people like the Beguines; people who had withdrawn from society and were really mystics.

And we have Jacob Boehme who was an incredible visionary and whose work I learned from.

Anne: Yes. I didn't know until I listened to the Embassy of the Free Mind, to a very brilliant woman who I think is in charge of the books explaining what happened to Boehme’s works, that they were rescued by a man in the Netherlands who copied the manuscript's word for word and manuscript by manuscript and saved all his work, which would have been destroyed. So it was thanks to a man in the Netherlands. I can't remember his name, I think it began with a B who rescued Boehme’s great works. And imagine him copying them day after day, month after month.

Faranak: That's kind of ‘taking the dust off the forgotten images’, isn't it?

Anne: Absolutely. Yes, and he had a vision of Sophia. That was the great focus of his writing, again the feminine aspect of divinity, although he may not have called her that. I really don't know enough about Boehme to say that.

Faranak: I wanted us for a moment to look at these images and experiences your shared in a historical framework, perhaps in a more playful way as these are obviously not the experiences humanity has had of the Feminine deity but they are interesting that you’ve chosen to share with us also because of these specific historical moments. For example the last one we just discussed of Boethius is where her image is already in decline, it’s in the dust so to say, there is a grief that comes over him. We could say that this is where the Feminine, Sophia was in decline, she was already ‘fallen’ so to say. When we go back to Apuleius and the vision of Isis, she is in her full glory really, there is nothing sinful or fallen about her. This also goes for the first one you shared of this great King which shows the authority of the goddess; it wasn’t out of the ordinary to receive a vision of the goddess. It wasn’t for everyone, but it was also not something to question I can imagine.

Anne: Yes. It was expected and anticipated that people would have these visions and that he would be told to build a temple in the dream.

Faranak: Later with Apuleius she's really in one of her most glorified images. And that might've been around the tipping point…what era is that again?

Anne: It was about the second century of the Christian era, probably around 180, something like that.

Faranak: So that would be the time that the image of the feminine deity starts to decline, really?

Anne: Well, probably because it began to be covered up by the Roman gods and goddesses and also by Christianity.

Faranak: I would like to continue the interview with a next question: What do you think that the importance of experiencing this feminine side of the deity is on culture as a whole or on a specific era?

Anne: Well, for instance, I'm thinking about the Cathars of the Southwest of France in the 12th and 13th century, their guiding image was Sophia. I don't know whether they had any visions of her but the church was called The Church of the Holy Spirit which is the church of Sophia. And the Troubadours took that teaching all over Europe in the 12th century to every country in Europe because, at the beginning of the 12th century, nobody had heard of the Grail for instance.

And at the end of the century, nobody existed who didn't know about the Grail. So they took the Grail which was a symbol of The Church of the Holy Spirit which gave out love to everyone, gave out the food that was needed by everybody to everybody. So that was a small cultural phenomenon if you like because it was wiped out by the Catholic Church and by the Inquisition.

And the Catholic Church had such power right away from then until the 20th century really, or the 19th century, that it was able to keep this tradition of Sophia absolutely underground. Because it came up again with Boehme, it came up again with the Rosicrucian Enlightenment in the 17th century. You can follow the thread right away from the 13th century up to the 18th or 19th century but the whole thing was underground because of the Inquisition.

It couldn't be brought up into the full consciousness of the culture. So Christian culture has been missing the divine feminine from the point of view of the Godhead, right the way through and that I think is an utter tragedy and is responsible for the mess that we're in now.

Faranak: Yes, and we might oversee the importance of keeping alive the existence of the feminine deity that these hidden traditions did. It really is almost like an underground museum keeping the images alive, even if it were a few people who still would be part of the movement. I think that is also really important.

Anne: Yes, and also the alchemists were part of this whole underground movement because their guiding divinity was Sophia also. So they took that on from the Cathar Church and it carried on right the way through European history. And that came out later on in what came in Hildegard of Bingen for instance, but she couldn't speak the full truth because it would have been heresy to say what she might've seen in her vision but she couldn't actually speak about it. She had to keep it to herself.

But we have the great vision of wisdom that she had there in the Scivias . And then we come on to the Russian Sophiologists which are very interesting, which I really didn't know about until I read this book called Sophia, by someone who's become a friend of mine: Susanne Schaup.

Anne: Yes. She wrote this marvellous book which I recommend to everybody. And she brings the Russian visionaries which I didn't know about before, who were quite extraordinary really. And one of them, here again, it's coming back. The Russian church has always worshipped Sophia, has always had an image in the great churches and in the icons of Sophia, as a great angel in some of the churches. She's shown as the angel of the apocalypse.

And this man; Solovyov who lived from 1853 to 1900 had a vision of Sophia at the age of 9. And again, at the age of 20 in the British Library when he was looking at books, he suddenly had this vision of her again. And a final one in Egypt where he went out into the night distress looking for her and fell asleep or fell unconscious and had a vision of her while he was lying there.

And she revealed to him, he says “the abundance of the Godhead, the eternal one” and that vision was never to leave him. And later he described his three visions of Sophia in a long poem, and he paid homage to her as his Eternal Friend, the Mistress of the Earth. It's a lovely title, Mistress of the Earth, the Woman of the Apocalypse and the Queen of Heaven. But then you have a trilogy of marvellous images of Sophia and I wish we could bring Sophia back into our lives really as guiding us now in our return to nature and our return to respect for the life of the planet.

Faranak: She's also connected there, interestingly to the apocalypse.

Anne: Yes. She's the woman with the sun with a circle of stars around her head.

Faranak: What a powerful Trinity; Mistress of the earth, the Woman of the Apocalypse and the Queen of Heaven.

Anne: He saw her really as Apuleius saw Isis; as the feminine principle guiding the whole cosmos. She is present within the whole cosmos as the life of the cosmos.

Faranak: Here, again, the importance of being brought up with images as he has been, in Russian churches, seeing ‘angel Sophia’. We see how important it is that she is represented, even if it's marginal.

Anne: Yes, I agree. Yes, absolutely because every church he went into, he would have seen her and he would have had perhaps sung hymns to her and things like that, with the priests and with beautiful music.

Faranak: Exactly. Even if it serves as even a small anchor for these visions to sort of find us or hit the note within us when we do receive her guidance. Because I think that a great loss of these images also creates— instead of revelations of the goddess—perhaps creates neuroses and psychosis for many people instead of being able to receive her.

Anne: Yes because it's completely shut out. And this ghastly scientific belief that has been guiding Western culture for 300 years says that the whole thing is without any meaning, that the universe has no meaning, no consciousness and that everything starts with our physical brain that has been a disaster for the imagination. It really has, although we've had marvellous images of the cosmos from the Hubble telescope. We have that, thank God which has stimulated the imagination and put us in touch with the cosmos again but we have no image of deity connected with that. And that is a tragedy really. And also we have no image of deity connected with the earth, with mother earth, as the Indigenous people have always retained the image of mother earth. And they pray to her and speak to her as a feminine image.

Faranak: So there's a question that relates to that and I had written down is; what do you think the influence on the psyche is and cultures when God is referred to as "He" with capital 'H' and perhaps only as "She" with capital 'S' when it's spoken as earth or nature. Because in your vision, you experienced the cosmic woman in the starry cosmos, in the heavens, and the heavens have traditionally been this place of Him, the bearded man sitting on a cloud.

I know in my own experience, as well as the women in my practice that when they have a vision of the feminine in the cosmos, the feminine being—the "She" with capital 'S' in the sky—it makes a huge impact on them to have the heavens not occupied by a Father but by a Mother image. It’s a huge difference for the psyche.

Anne: Yeah, well, it's very interesting that the "Our Father" prayer was originally an Aramaic one and Jesus or Yeshua as he was called in Aramaic would have spoken the words which were to the Mother-Father of the cosmos, not the Father. In Aramaic, the word used to address the deity was Mother-Father. And of course, Mother got lost.

So we've come down to "Our Father which art in heaven" instead of our Mother-Father or our Father-Mother whichever way you would want to put it. We've lost that feminine element right there in the very biggest, most important prayer. And in Aramaic, it would have been utterly different because the feeling would have been different and the imagination would have been different. The image would have been utterly different.

The Aramaic language is very rich and it goes on for much longer than the Lord's Prayer, — the actual prayer in Aramaic. And it's full of the imagery of nature and the cosmos and everything else really, it included everything. And it worries me a bit that earth is associated with the mother as earth only, instead of the cosmos.

Faranak: Exactly.

Anne: Because it excludes the All and the entirety of the All and this is what Solovyov understood that she revealed to him the Eternal One, which has both male and female. And this is what we have to get back somehow. Susanne Schaup in her book makes this important conclusion in regards to this problem:

"As long as the feminine is not located in the Godhead itself, as long as it is subservient to God, the creator Sophia cannot act from divine empowerment in her own right. The sacred wedding has to take place within the deity as Hildegard saw but dared not say."

So there we have it really, that is the key to everything. We have to restore the image of both deities to deity.

Faranak: Otherwise, she will still remain submissive to 'He' as the ultimate Godhead and 'She' is just creation or just the earth.

Anne: Exactly, yeah. Going to be associated with the created world but not with the invisible world, the divine world.

Faranak: Yes. And I think that is really disempowering for the feminine.

Anne: It is, you're right. Absolutely, dead right, it's disempowering. In my work, it has been to bring back the feminine and yours is as well. So, you know, we're working together on this same goal as it were. Actually, I had a dream last night.

It was about a man and woman who had come to stay bringing a baby with them and they were in a sort of guest suite. And they got up earlier than when I was ready to receive them. And then they were in a car later on, the father had gone off shopping. I was there with the mother and the baby and the woman handed me the baby which was wrapped in swaddling clothes almost completely covered and put it on my left arm.

And I looked down at the baby, it was a little girl. And I said to it, "what a beautiful baby you are." So maybe this is the feminine coming back, it's still infant, you know, it wasn't more than a month old.

Faranak: Oh, that's sweet image.

Anne: And she left me for a minute, she'd gone out as well and said, "can you hold the baby while I just go and do something, I'll be back in a minute." And I was worried that I would be left holding the baby and she wouldn't come back for it. That ties in with today's talk without question so it's a lovely dream.

A baby girl and dressed in white with lots of coverings, several layers of white coverings with just her little head buried in the coverings so to speak like a hood.

Faranak: It's almost like a cocoon.

Anne: Yes, exactly like a cocoon. That's right. That's the image to go with our talk today.

Faranak: So going back to our problem and where I wanted to go with my previous question. If humanity is needed in this process, let’s say the final stage of Rubedo; ‘redeeming the cosmos ’, or redeeming the Godhead itself. So humanity needs the Godhead but the Godhead also needs humanity to experience itself, to know itself….

Anne: That’s right, this is what Jung said. The human being needs the god-head but the god-head needs the human being to know itself. Jung understood that God needs man’s help to understand who He/She is.

Faranak: So perhaps if the Godhead can experience itself as Her, then maybe that will as your friend Susanne writes in her book Sophia, maybe that can restore the incredible imbalance that we have and are experiencing. Because it's the Godhead itself that is missing this experience or that has lost the experience.

Anne: Yes. I think that you put your finger on a very, very important point. And I hope this comes through because if that's missing—if a the Godhead doesn't know herself and himself to be the wholeness that we hope He-She could be, how on earth are we going to change anything on the planet?

Faranak: Exactly, yes. So it brings us back again to this idea—it’s what I live by, as we say in Sufism: “it’s not for us, it's for the sake of the beloved”. So for the sake of the beloved which is also the sake of this world and everything in it, we retrieve this experience of the Godhead itself as feminine so that everything may come into balance.

Anne: Yeah, it's important to restore the balance. That's the most important thing and Jung saw this as enantiodromia: when the pendulum has swung too far one way, it's got to come back to the middle. This is what we need to do, bring it back to the focus of the centre.

Faranak: Yes. So maybe we should be calling the divine feminine not Goddess per se, but God as Her, the divine as Her - to bring back this language that has been one-sided.

Anne: Well, it’s difficult because in other languages you would have the ending of ‘naan’, which in English we don’t have. In French you would say ‘la déesse’ which is a feminine noun.

Faranak: Yes, we’ll see how the language will want to shift. But I do think it is important because I know personally when I read a book and God is constantly referred to as ‘He’, I get annoyed…it can get under my skin.

Anne: Yes, it’s a habit. It’s a 2000 year-old habit and it can be changed. Because it was changed before into what we have now. We can do the sacred unity, the sacred marriage which is the most important idea to hang on to.

Faranak: Yes, Him-Her. Well…I think we have come to the end of our interview.

Anne: Okay. Well, thank you so much for inviting me. It's been most interesting for me to have somebody to share my thoughts with and to listen to your thoughts. Thank you so much.

Faranak: Thank you so much. And I'm sure this is going to be of help to many men and women who are in search of this balance in their experience of the sacred. Thank you so much.

END INTERVIEW

The Tear of Ereshkigal

Collective poetry from Anima Mundi School students.

This poem is a collective effort in the myth-cycle of Inanna-Ereshkigal of our core course Reclaiming the Mythical Feminine - class of 2022. Poem recital by Kate Alderton.

The Tear of Ereshkigal

Listen

from the Great Above

she opens the ear to the Great Below

Open

from the Great Above

whispers

of mist call

to the sorrow of the Great Below

Feel

where sorrow and agony crack

hearts

into unknown depths

Ache

what does the Queen of Death birth?

her barren womb

bears the seed of all life

Surrender

She, the one who knows sacrifice

is sacrificed

is sacrifice,

demands

pulls

longs

deserves

justice of the heart

Tear of Ereshkigal

great is your praise!

Bathe

Drench

Moisten

The salt sharp crystals of life.

Holy Ereshkigal

great is your praise!

The Presence of Story

An essay about the art of forgetting and re-membering story by Gauri Raje.

by Gauri Raje

The first Indian story I told in public was born out of laziness. For a long time, I resisted telling Indian stories anywhere. I told myself that it felt disingenuous. I was beginning a new life in the UK, a new land. The circumstances of leaving the land of my birth were sad, and I had been unready to leave. But I was not ready to stay back either. Telling stories from India felt untruthful. I lived in that limbo state or a long while.

Then at a storytelling workshop, after a good lunch, I was given two hours to prepare and tell a new story. I can’t say whether it was the effects of that nourishing lunch or just the warmth of an English afternoon, but my laziness led me to the library and to a section on stories of women. That laziness led me to stretch out my arm and pick a compilation of stories from around the world where women were the central protagonists. I picked them, not because of any idealogical fervour; laziness was seeping through my veins. I picked them because I identified myself as a woman, and so gave myself the entitlement to tell a story of a woman. Not the most auspicious of beginnings.

The story I told that afternoon was nothing like the story of the page of the book I had picked up in the library lazily. It surprised even me - where did those images arrive from? Perhaps the only link might have been that the book stated the story to be from central Maharashtra - the region of my father’s ancestry. I had never visited this place; nor had my father after his childhood and nobody in the family knew if the village still existed or was swallowed up by the urban conglomeration of Mumbai and Pune. There were no images of our ancestral region spoken about in family gupshups. The story I told resonated in my body as I told it. It’s rhythms were easy when I spoke it - and very different from the story I had read. It was a story that grew, shapeshifted and fell back into the story I had told the very first time. Something like a song; a raga - a base skeleton that was fleshed or changed form with every telling. Few stories I had told until that time had such arrivals, growing and departures while staying the same story all the time.

Of course, I was pleased and ego-boosted.

Four years later, I embarked on a journey of finding out more about my family. Most of those from my father’s generation, siblings, cousins, aunts and uncles had passed on; I had just my youngest aunt, all of 85 years young, to speak to about any memories she might have had about her parents’ village. She had been 4-5 years old when they visited the ancestral place for the last time, and remembered very little. Personal memories are a very specific reservoir; so I began to enquire about a larger pool of collective memories of the family, stories told in the village as she was growing up.

She did remember a story—something told as a story to her as a child, an anecdote that had happened to her aunt & uncle, my grand-aunt & uncle, and was perhaps a few sibling/cousin lines removed. As she began to tell the story, the contours of a very familiar story arc emerged and magnificently, so did the details of the landscape, chillingly close to my naive descriptions in the story that I had been telling for the past four years in the UK. A family story that had entered collective memory, and then egged on, no doubt by a medium of a colonial pen, found itself into an anthology of English-language stories of women.

My journey with this story raised some interesting questions regarding my relationship with this story. It is well-known that fragments of ancestral memory travel down generations. While there is enough and more literature, and studies available on the transmission of traumatic memories; there is not as much material on the movement of other memories over generations.

Over the many years of storytelling, I have begun to sense a difference between a story told because it fascinates the teller and a story that springs out of the depths of their being. The latter often takes even the teller by surprise. How did they know to say that particular detail? Why does a particular story obsess or haunt a teller, even when they may not like it? Fascination with a story may only be a tip of the memory; at times, it feels too wilful as if breaking into a horse to ride it. I am not sure how much it allows the teller to move with the story, rather than making the story do the teller’s bidding. Through the above example I look at the full circle that a story may make through personal and more historical elements, wherein a personal story enters into collective memory to return to the familial lineage down the generational line.

The story arc about outwitting dacoits is not new. It was a constant and everyday part of the life of those who lived in dacoit-infested regions. Walter Benjamin speaks about the storyteller as one that relies on a bedrock of the ability to share experiences, rather than pass information (1. Benjamin, ‘The Storyteller’). In other words, a story like the one I mentioned was grounded in not just the sharing of one experience of outwitting dacoits, but multiple such moments. Whether it was multiple incidents that constellated into a story as it passed over many tongues through ages; or there was a seminal incident that created a template for a story to pass over generations is a matter of speculation. It is a matter of storyfy-ing, in a way.

Walter Benjamin also says something really prescient about the assimilation and remembering of stories by individuals and collectives. “This process of assimilation (of story), which takes place deep inside us, requires a state of relaxation....If sleep is the height of physical relaxation, then boredom is that of mental relaxation. Boredom is the dream bird that broods the egg of experience...The more self-forgetful the listener, the deeper what is heard is inscribed in him”. In a world that conditioned to ‘preparing’ and/or ‘rehearsing’, this may seem counter-intuitive. However, there is some truth that Benjamin touched upon—it is often when one is not looking for a story that a story arrives that lodges itself in one’s remembering. This state of boredom becomes the ground for remembering and recognition that is deeply intuitive.

Benjamin’s description also brings to mind the re-membering which is part of the great myth of Osiris & Isis. The myth of Osiris is the archetypal myth of transformation and becoming. It has been known in different oral traditions that during our lifetimes, that which is important may be forgotten; but it never completely disappears. The mind may forget but body memory is not to be taken lightly. Osiris is regarded as the spirit of the soil that animates and regenerates it through creating an awareness of the body. It is through attuning into the body’s rhythms that it is possible to create space for re-membering. Dreamwork, body and art work are ways of moving from everyday rhythms and ordinary time into a deep time and imaginal space that allows tuning into to what might be called inner stories—a realm of forgetting. It allows one to be deeply in a moment rather than in the consciousness of being embodied.

In the myth of Isis & Osiris, the death and dissolution of Osiris repeats a few times. Death is not just a moment, nor is regeneration. Accompanying the passage of Osiris into the underworld is the journey of Isis—his beloved, his sister and wife. Hers is a journey from shock and abandonment into a persistent tending to the search, protection and care of the body of her love, brother and husband. She becomes the mediator between and curator of both the world of the living and the world of the dead. She journeys along the life-blood of Egypt; along the Nile river to recover the dis-membered parts of her husband’s body; and she re-members those parts along with Nephthys, her sister and the Goddess of mourning rituals. It is her labour through mourning and then embalming her husband’s body that curates his journey through to becoming the God of the Underworld. This is her service to death. In the meantime, she also brings up her and Osiris’s child to make him a worthy king of the lands of Egypt, and of the world of the living. This upbringing would have also included re-membering or curating the memory of his father, Osiris to become a young warrior taking on his uncle Seth in battle and defeating him, thereby avenging his father who had been killed by Seth. The circle is now complete, and Osiris can move into his Underworld domain to fulfil his own destiny as Lord of the Underworld.

The myth of Isis & Osiris always reminds me of an important aspect to tending to mythic journeys - the necessity to submit. Isis’s journey of re-membering plays out not only due to her determination; but equally her submission to what cannot be recovered from, literally and metaphorically, the river of time and being. Not all parts of Osiris are recoverable—his phallus is swallowed by the fish of the Nile. Isis re-members Osiris by refashioning his phallus from wood or clay (the versions differ on this). They need to be re-fashioned.

Here is the relationship between forgetting and remembering spelt out—there will be aspects that cannot be recovered with story or storied journeys. Submitting to the forgetting and/or re-fashioning is part of the life of the story.

Re-fashioning can very easily fall into the understanding of innovation in our progress and uniqueness obsessed world. As I worked as a rookie apprentice storyteller, I too cogitated and puffed up my chest in anticipation of how wonderfully I could innovate, and suffered crushing disappointments when I could not. Over time, working on my great-aunt’s story and later, the Osiris & Isis myth, another understanding of re-fashioning began to be, well, re-fashioned.

Re-fashioning is also the work of maintainance. The maintainance of ritual, like Isis, and the maintainance of the story itself, like my great-aunt’s story. For those of us who have worked with rituals, either grand rituals like marriage, death or making ceremonies or everyday rituals, like doing your yoga practice every morning will know that these are not about the exact replication of actions or processes. As is the way of time, things get lost, go missing, get broken—maintainance, even in ritual, is about finding the elements that will allow the larger sequence of events and the larger narrative to carry on. This is what Isis is doing in re-fashioning the missing phallus. A creation that is a maintainance, that is in service of. This is what happens each time I work with my great-aunt’s story.

Working on a story is, more often that not, traveling with a story as it finds different forms, different layers and facets to the characters within a story. With the story that I mentioned in this essay, it was an experience of working with the story. As the time I spent with the story grew, and the number of times I told it, there were different facets to it that became prominent. Through it, I was learning about relationships within the socio-cultural milieu of the place of the story and its ecology. Knowing that the story was from the Deccan, additionally allowed me to not only research the story but work with the fragments of memory of the place that I had gathered through my father’s and his siblings’ stories and reminiscences. Since that family was no longer living, moments of ‘doing nothing’ allowed fragmented memories to float up. Research follows that bubbling up—initially for verification; later to understand the place and a network of other stories from the place. The story then becomes a portal into meeting a place and people. It is then, as part of this research that my conversations with family about family stories and memories began.

The telling of this story and getting familiar with the potent moments in the story has been a long journey into understanding the social, ecological and cultural landscape of the story. It gave me a sense of the width and breath of the different characters that inhabited the story. Hence, it was not just about creating the character of a particular type of woman or man or bandit. That arrived as I got to know the different characters of men, women, farmer, bandits or market places that cropped up in the story. Enough to know the ecology of the relationships between characters so that a certain character of a woman or man would not be present in that particular ecological landscape. This is how the story began to arrive for me after the first telling. It then, was a delight to find it recounted as a familial story; however, in its telling it had also become a story of the many people who lived alongside bandits in these villages.

The overlaps between my description of a village I had never visited and my aunts description of our ancestral village is a mystery that continues to remind me that often a story does not have to be worked on, but let it lie within oneself to begin to reveal itself.

References:

1.Benjamin, Walter. 2019. The Storyteller Essays. New York: New York Review Books.

2. Cavalli, Thom. 2010. Embodying Osiris: The Secrets of Alchemical Transformation. Wheaton: Quest Books.

Through the Gates of Inanna: Birh as Feminine Initiation

An essay about birth as feminine initiation by Suzanne Schreve

by Suzanne Schreve

A year before, almost to the date, a child died in my womb. Now one is being born. I feel the energy in my body change. My uterine muscles no longer contract upwards but ripple down. It catches me by surprise. There comes the second wave. It has started; my womb is pushing the baby out. I feel relief.

When the process of birth shifts from opening the cervix to moving through it, the pain subsides. In mythology, it is the opening of the doors to the underworld that brings the initial suffering. In the myth of Inanna there are seven gates to pass before she completes her descent into the underworld. At each gate the gatekeeper, Neti, beats and strips Inanna of her clothes and jewellery.[i] When she finally arrives at the gloomy queendom of her dark sister Ereshkigal, Inanna crawls on all fours wearing only the dirt on her skin.[ii]

Prima Materia

The mill of the underworld keeps churning until you’re nothing more than husk. It empties those who knock on its door from all false images to the base ingredient, the prima materia, a primal instinctive animal self. Inanna’s stripping down at each gate represents this grinding down of the ego: her earthly persona, any sense of self-identification, any false attachments. It seems that this is what the contractions do in birth before it moves into the ‘pushing’ phase. Most women experience it as painful, an excruciating gut-wrenching horror at the most, or at least as intense. I have heard women describe it as glass shattering in their backs. My first birth literally floored me.

During that first stage of contractions the womb is physically opening a gate and it takes as much strength to open a gate as it does to keep one closed. The womb is the strongest muscle in our body, keeping the cervix shut to safely carry a baby whose average weight at the end of nine months will be 3,3 kg. Add in the placenta and amniotic fluid, the womb holds another 1,5 kg.[iii] By the end of those nine months, the force with which the womb contracts, creates a dynamic change in the woman herself. She has now become the vessel for the womb. Some call it true labour, when contractions last up to 90 seconds every four minutes or so. To hold this force of nature, to be a vessel for it, may require all the capacity you can find in yourself.

When I was pregnant seven years ago, I did not think of this. I watched and read all these wonderful stories about orgasmic tantric birth and quickly decided that that was the birth for me. I made all the preparations to facilitate a cosmic experience of birthing bliss feeling confident I too would enter womb Walhalla. We ordered a home bath. I had a birthing ceremony. There were candles, incense, wind chimes and Tibetan singing bowls. We did tantric breathing exercises, hypnobirthing, perineal massage, and acupressure. At ten pm my waters broke showing blood. I ended up in hospital and forcefully pushed out my daughter seventeen hours later while being hooked up to an oxytocin drip.

That long night, morning and early afternoon, each contraction pulled on another tightly wrought string of feeling abandoned, scorned, attacked, misunderstood, victimized, and overwhelmed. Throughout most of those seventeen hours, I felt like a wounded animal, and acted like one too. I did not experience bliss, only temporary relief. Just like Inanna who demanded entrance to the underworld, a realm outside her jurisdiction, I too had demanded an experience that wasn’t mine to command. All I could do was endure.

In birth, the increasing strength of contractions is the labour of initiation.

Although I thought I had prepared as well as I could have, no one can fully prepare for initiation. You’re not meant to. It is supposed to overwhelm so it can blast away all the congealed misconceptions. If there remains too much familiarity for the ego to hang onto, it will hold the lid on the unconscious, burying both our trash and our treasures.

Door to the Underworld. Clay plaque, Mesopotamia. Isin-Larsa-Old Babylonian period, 2000-1600 B.C. Paris, Louvre.

The physical pain and exhaustion that we experience during labour push us into the deep. The physiological aspects of labour illustrate how physical pain and exhaustion wears down our mental capability. We move into our primitive brain and constellate a flight or fight reaction exhibiting emotions of anxiety, panic, stress, and fear. In Jungian terms, you could also define this as an encounter with the shadow. The typical shadow shows itself in our reactions as primitive, instinctive, fitful, irrational, and prone to projection. It is our dark side, that which we do not want to be nor accept about ourselves, but this can be both something we view as negative or positive. During my first birth, what I experienced was the opposite of what I had ‘envisioned’.

In Inanna’s story, it is her sister Ereshkigal who personifies the shadow. She is the Queen of the Underworld. When Inanna arrives crawling at her sister’s throne, Ereshkigal casts Inanna the eye of death and has her lifeless naked body hung on a hook.[iv] Such symbolic death is indispensable for spiritual life and must be understood in relation to what it prepares; birth to a higher mode of being.[v] Earlier in the story, Inanna had caused the death of Ereshkigal’s husband through an act of inflated egocentric greed and play for power.[vi] Ereshkigal, pregnant and now without her child’s father, acts to remind her arrogant sister of the grounds of earthly being; of grief and loss, of pain and humility.

While Inanna’s flesh rots away for three days, something remarkable happens. The ego-self represented by Inanna becomes subservient to her shadow sister Ereshikgal, and not without conscious intent. Before Inanna made her descent, she had instructed her consort Ninshubur to call for help if she were to stay away for more than three days. It illustrates a knowing of the underworld tidings and its obscure process of gestation. The killing of Inanna can then be seen as the choice to submit to the organic wisdom of nature. In the rotting of her flesh, Inanna is consumed by the fermenting processes of death. Fermentation converts raw materials into a desirable product that sustains new life. Here Inanna’s body as raw material, or prima materia, is transformed into something useful, into new consciousness. The process requires an active passivity of the ego-self and a submission or acceptance of life ’s circumstances as it is presented in the moment. Instead of fighting whatever comes our way, we heed to the call of the underworld and let it shape us, let it birth us. In this moment of submission, whether made consciously or not, the shadow, which normally acts passively in one’s consciousness, now has the active role of birthing something anew. As Jung says:

“We must…..let things happen in the psyche….This is an art of which most people know nothing. Consciousness is forever interfering, helping correct, negating.”

— C.G. Jung 1958, as cited by Lowinsky 2016)

While Inanna’s corpse decays, Ereshkigal goes into labour. She leads the way into new life. This is feminine destruction with the purpose of creation, fundamental to the workings of the crone energy that stands firm at each threshold of feminine initiation. Woodman and Dickins (1996) describe this energy as

“the Goddess who gives life is the Goddess who takes life away. . . . we hold the paradox beyond contradictions. She is the flux of life in which creation gives place to destruction, destruction in service to life gives place to creation.” [viii] The crone lends her helping hand only to discard us, testing inner faith; a yielding to build endurance, which allows us to give in even more.

Death and Rebirth

The psychology of initiation finds its roots in these death-rebirth myths, where the archetypal processes of death and resurrection can be utilised in the task of transformation and growth[ix]. In almost every ancient culture you can find a myth of the dying-and-rising God. Isis and Osiris, Persephone and Inanna, but also that of Buddha and Jesus. The death turns into birth story ‘corresponds to a temporary return to the primordial Chaos out of which the universe was born, while ‘rebirth’ corresponds to the birth of the universe. Out of this symbolic re-enactment of the creation myth, a new individual is born.’ (Eliade, 2017)[x] The rituals that re-enact this great shift in cosmic order as a reflection of a shift in consciousness are mainly lost to us. In the West, we are mostly dependent on nature and life to shock us into maturation. Childbirth presents an opportunity of not only initiation, but also one to enter consciously - to a certain extent. You can either work against the tide or go with it.

Where the tide takes you may neither be relevant nor redundant. One of my clients’ wishes for a natural birth took on a different meaning as we explored her dreams during her pregnancy. While she hoped for a birth without medical interference, she also expressed a need to be in the hospital as it made her feel safe since it was her first child. As we worked with the images of the unconscious, she relaxed into the wisdom of her own body and in the medical knowledge of the hospital. She expressed her wishes as much as she could, and as she did so, dream images of power animals, such as lions and horses, became regular visitors. In our last session together before she birthed her baby, she moved into the image of the horse, feeling its strength, walking and standing as the horse, experiencing its clarity while feeling grounded in her body. Her waters broke as she motioned out of the experience. A week later she recounted her story to me. The birth was long and arduous because the cervix did not dilate. When her gynaecologist asked her if she wanted to continue natural labour, she felt herself connect into a clear mode of thinking, much alike she had experienced while ‘being’ the horse. She gave in to what her body told her and asked for a caesarean. As they wheeled her into the operating room, she not only felt present in herself, but surrendered into the loving arms of the four women helping her. She describes the birth of her daughter as miraculous, loving and gracious. She could not have imagined that a caesarean birth would feel so natural. She had surrendered to the tide.

For the birth of my second child, I made similar preparations to my first. We hired a birthing pool, a friend mixed herbals and tinctures. I watched videos with my daughter and reacquainted myself with hypnobirthing. I performed rituals, I received massages, and I took the time to ease into my body. But I didn’t do it with a singular idealistic focus in mind. Pain creates muscle memory and endurance builds character.

This time, I merely followed the currents of my instinct and my dreams as they entwined into consciousness.

Looking back, I watched hypnobirthing videos because my mind needed to know what my body was doing so that when I was in pain, I could marvel at the brilliance of nature’s design instead of sliding into victimization. I watched birth videos with my daughter, both the relaxed ones and those of women screaming in pain, because I wanted both of us to be prepared for birth as it is and as it can be. I went to a massage therapist, because I needed to be touched and my husband simply did not have the time to do it. It was on the massage table that I felt my body become Earth, my thighs her hills, my blood her water. My body was hers and the birth of my daughter my gift back to Her. From that moment, it wasn’t just my experience anymore. I honoured the Goddess through ritual, but mostly by honouring her dark chthonic, earthy wisdom. By ‘getting out of the way’ just as Inanna had to when her corpse was flung dead on a hook.

It is also here in the story where help from the upper world leads to the rebirth of Inanna. While Ereshkigal endures her labour pains below, Inanna’s consort Ninshubur runs around looking for help above. It is Enki who finally turns up with the goods. Enki is a multifaceted God and holds amongst others the virtues of mischief, magic, wisdom, water, and male virility. Enki is said to be an Earth God, having made a full descent-ascent to the Underworld, and often chooses the path of compassion, forgiveness, and wisdom. At Ninshubur’s plight and with a father’s love for a daughter, Enki scrapes some of the dirt from underneath his fingernails, which become two sexeless beings, or demons, and sends these to Inanna. The beings transform into flies, so they can enter Ereshgikal’s cave unseen carrying both the water and bread of life for Inanna’s revival. The flies on the wall don’t do anything besides groaning when Ereshkigal groans, moaning when she moans.[xi] I have seen this behaviour replicated by my one-year-old daughter in response to her crying elder sister. As the eldest throws herself in primal fits of crying over lost candy or anything she feels a distinct ‘loss’ for, however trivial it might seem to adult eyes, her little sister will come up next to her and echo the sounds while patting her back, until hands reach out for embrace and crying soothes into simmering sobs. In this simple yet unexpected show-up of support, Ereshkigal softens as well and gifts them anything the flies may wish to take. Of course, they want the corpse, and Inanna finds her way back to the living. It could be argued that in the surrender of the feminine, in the complete softening into Eros, the integrated masculine principle responds. This masculine is in touch with both the earthly and cosmic realms and descends with a clarity of compassion that extracts light from darkness, and paves the way for ascension.

When starting the path down into the initiatory realms of birth for a second time, I passed each gate releasing something. A misplaced ideology, a sense of false ownership, the fear of losing control. But it was in the peak of labour pain that I truly gave in. Giving in not by slumping into self-pity, but by giving into a power much greater than I will ever be able to fathom. The Goddess works in mysterious ways, they say, and the steps that take one from contraction into expansion work differently for each person, for each new descent. She had been leading me, hinting of what was to come, or could be, through a myriad of ways throughout my pregnancy.

I had tiptoed the edge of the inner and outer worlds for months. My brain had become soft and my experience of the world around silenced. This state of being, or birth energy, gradually descends in and around a woman’s body, a serpentine coiling, but with the gentle touch of a cloud. In the last week, my uterus had been kneading the cervix with increasing intensity each day, announcing the onset of labour, but at the last moment subsiding.

“I dream about little elephants walking along a bank. They turn into young children and are accompanied by a sweet but strict elderly woman. Now they stand in the centre of an auditorium shaped spiral. A girl with curly blonde hair runs towards me. We hug each other at the outer rim of the auditorium, so happy to see each other, but it isn’t time yet as the old woman calls her back.”

The next day our daughter was born.

THIS IS OUR STORY.

I tell my husband it could happen tonight. He lays a towel underneath me, just in case. Ten minutes later we hear the muffled sound of a balloon popping. Warm water trickles down my leg. ‘What was that?’ he asks. I giggle as a flood of oxytocin rushes into my bloodstream. “My water broke,’ I reply.

The sequence of events mirrors the first time. Water breaks at ten pm, contractions start immediately. But this time there is no blood.

My husband goes downstairs to set up the birthing pool while I go inside, down into my breath. It feels intense so quickly. I wade in and out of the bath upstairs, finding solace in weightlessness. Nobody records the rhythm of my contractions, only I know, sort of. Although I have learnt to elongate my outbreath to induce calmness, there are moments I want to run away from the pain. I automatically start to groan low tones. It is not something I practiced or read about, it’s what my body wants to do. I remember this from last time and think back to those long seventeen hours while I hear my mother climb up the stairs. She’s been called in to look after our eldest.

dream image of ‘woman by fire’

My husband welcomes me down two hours later. He feeds me tinctures and warm tea that I hardly notice drinking. The birthing energy amazes me again. How it centres and pools around, creating an even stronger primal instinctual silence as the mind completely fades. The part of me still consciously present condenses into a singular point of focus, I can only just about make out the candlelight and altar. A week before, I received a blessing ceremony here, in this same spot. The drawings of the women hang above the altar, including my painting from a dream experience a year before.

Suddenly I am fully aware that I am in another dimension, but not the same as a dream. She is in front of me. A beautiful native elderly woman in a Maria cloak made of fire. She looks powerful in her silence. Not necessarily peaceful, but more of a focused silence, in surrender to this fire. This is necessary, I know, the fire. She is showing me this, that she has to go through this. It all happens very quickly, the thoughts, the experience. The reality of it scares me and I throw myself back into my body. I re-enter through a burning heart, waking up underneath the stars where I am camping out with my daughter. I hear the words Anima Mundi .....

My husband sits behind me in the pool while I feel hot energy enter my crown. Each time it funnels down into my body, it initiates another big contraction. By watching the videos, I know what my womb is doing, contracting out and up to open the cervix. I don’t do much, rather as little as possible. The wisdom of my body, of the Anima Mundi, is at work and I am just an observer of something completely magical.

Yet every so often, the contractions feel too much, that I cannot bear them all.

Especially when my husband pulls away to do the necessary things. Changes, however small, puncture a hole in my bubble. The familiar feelings of abandonment and victimization creep up again. I try to breathe through it, but it has only been three hours. I ask my husband to call our midwife. I want drugs.

With her thirty years of experience, she listens to my moans and concludes I am not yet experiencing any ‘peaks’. “Mindset”, I hear my husband repeat. “Call back in an hour.” Right, no drugs then.

My midwife’s cool and distant words sentence me to the imprisonment of my body. I am bound within its pain and any struggle against it, any notion of being able to cope, now fully disappears. Something in me knows that the only way out is fully in. I can only submit; all of me needs to bow down.